Threat to Seeds is Threat to Peoples’ Sovereignty

The Question of "Seeds"

This is one of the most important essays for the readers and activists who are connected to Chintaa. For activists thinking and organising for a post-imperial post-capitalist global community, this essay is fundamentally important because of the emphasis on the question of local and indigenous cultural practices, farming techniques, and strategies for the creation of economies of resistance. This essay shows why Nayakrishi Andolon (New Agricultural Movement) is not about having a rhetorical stance against imperialism based on an European ideological account, but rather, conceptualizing a notion of resistance by placing emphasis on a new kind of sovereignty which derives from local and indigenous knowledge-systems. Our study circle(s) on the ground in Bangladesh and the larger subcontinent, in diasporic communities, and in global solidarity-based movements, are absolutely interested in studying important texts that come out of the European discourse (e.g. Marx, Foucault, Derrida, Heidegger, Lacan, etc), but we also understand that resistance movements will have to be contextualized within our own political history, rural cultures that question bourgeois dependency on urban centralization, and religious interpretations that are consistent with the day to day struggle of the people. We have to counter fascist secularist tendencies to whom 'seed' is nothing more than a sanitised agricultural 'input' for consumption bearing no spiritual or metaphoric meaning in our life or in constituting our communities on a radical premise in order to go beyond the present crisis of human existence.

Farida Akhter's relentless work in the area of peasant movements and her interest in effectively using "seeds" as a mobilizing/organizing tool must be taken into consideration by the larger movements against the hegemonic discourse of the West funded and supported by multinational corporations.

We must realize that in order to think and work along the mass line we have to focus on the question of seeds.

You may also read 'Seed shall set you free...'

[Editorial commentary]

Threat to Seeds is Threat to Peoples’ Sovereignty [1]

Introduction

In recent years the concern to defend food systems, natural resources and the conditions of food production shifted the meaning and political use of the notion of 'sovereignty'. Environment, ecology, agro-biodiversity and related knowledge practices are not only means for food production, but conditions of life. Explicit concerns have been expressed against the State, corporations, causal scientific accounts, uncritical faith in technology, and neo-liberal economic policies and trade regimes that together have been breaking down conditions that are necessary to conserve, regenerate and enhance life activities. In this context, seeds re-emerge as a powerful metaphor and symbol of resistance against global capitalism. Seeds also place new emphasis on historically consistent indigenous systems of knowledge.

The State initially transformed local into national and subsumed local under global and in the process undermined agriculture and rural agrarian life in favor of urban industrial civilization. In the era of globalization the rift has further shifted from national to global, accelerating the final destruction of the 'local' and the 'concrete'. The new call to 'sovereignty' therefore cannot be understood within the conventional paradigm of sovereign nation state defined as the ability to decide in times of 'exception'. The call for 'sovereignty of the 'local' against the 'global' is a qualitatively new phenomenon and intends not to return to pre-global local life or life styles but raised as a strategic slogan to reconstitute new political subjectivities to reinstate the notion of community as the prime political mover to defend and ensure conservation of life support systems and biological survival. Communities cannot leave the responsibility of food production to the State or to corporations. Industrial 'progress' has historically destroyed farming communities and farming as a lifestyle; food production as a sensuous activity, experience and knowledge practice through metabolic interaction with nature has also been obliterated. Modernity and secularization of systems of knowledge marginalized farming communities in the global South as traditional and obsolete. The call for sovereignty interrogates these issues and challenges the conventional paradigm in order to defend communities from destructive processes and practices. It is clear that domination over the postcolonial South in global politics will be about the question of control over food production and natural resources. Food production is directly related to the question of seeds. Therefore, the call for new sovereignty is a call for seed and food sovereignty.

People in the Asian region are threatened by systematic aggression on food production and particularly the production of rice which is the staple food of the region. It provides food for the 4 billion people in Asia, which is about 60% of the world population. Unfortunately political activists in this region have not identified the threats posed to seeds as one of the major threats against the sovereignty of the nations. Economic basis of modern political state is grounded on the destruction of farming practices and communities.

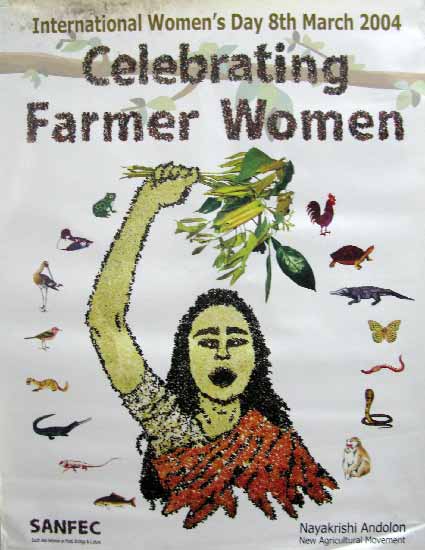

A poster of the South Asia's peasants movement celebrating farmer women on International Women's Day organised by Nayakrishi Andolon in collaboration with South Asia Network on Food Ecology and Culture (SANFEC). Constituting a post-imperial global community depends as first step in developing the capacity to bring together the farming community of South Asia in line with the biodiversity-based ecological practices as lead and practiced by Nayakrishi and SANFEC mebers. The stength of this movement lies not only at the level of organisational capacity but to re-define women's movement. The contributon of femeinist movement in imagining a new world is undobtedly a new element in global politics, despite the backlash it has been suffering recently for various reasons. In this context an unique event took place in Bangladesh when the peasant movement initiated to widen the notion of 'women' and women's movement by bringing the farmer women at the center stage. It was a significant shift from the conventional urban and middle clas notion of 'women' and brought to the forefront the concrete issue of seed, biodiversity, ecology and environment and most importantly the value of local and indigenous knowledge system. Conservaion, regeneration and unfolding of the possibilities of life as the central question of the the present day poliics was the implicit theme. It is time that women of the world take note and start celebrating farmer women who kept us alive for millenium by their knowledge, wisdom and practices.

Growing food by farmers is integral to keeping seeds for generations. Farmers regenerate and expand their biodiversity and genetic base. This is the main characteristic of this region, Asia. In Asia, farming is the major livelihood for the people. Any threat to farming is a direct threat to food production as well as livelihood options. Threat to farming can come from agricultural policies and practices that deprive the farming communities control and command over seed and genetic resources.

We will discuss here how the sovereignty over seed and genetic resources is lost through agricultural and technological policies that have been aggressively promoted since 1950's by USA and other developed countries.

Green Revolution

In the post-World War II period, the powerful industrial countries understood very clearly that the strength of Asia was lying in their agricultural practices premised on the wealth of diverse seed collection, particularly of rice. It was already known that the Oryza Sativa, broadcasted or transplanted exists in numbers not less than 120,000 varieties. The top ten rice producing countries in the world are in Asia. These are China, India, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Vietnam, Thailand, Myanmar, Japan, and the Philippines. In addition Brazil in South America is also producing rice. Yet, a new High Yielding Variety (HYV) Rice was introduced by the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines and was financed by Ford and Rockefeller Foundations. Why a new variety needed to be developed when there were so many varieties already available? There were many varieties that have been performing very well in terms of productivity expressed in diverse and complex ecosystems. In contrast HYV required homogenized production conditions and use of an expensive package of chemical fertilizers, pesticides and irrigation. Aggressive introduction of HYV created the market for the chemicals produced by the agribusiness and made farmers dependent on the inputs. Food production, particularly rice production became tied to the chemical companies, and diverse landscapes that have been nursing thousands of species and varieties were reduced into homogenized fields.

The introduction and imposition of the new ‘chemical dependent seed’ came through the foreign assistance received from the World Bank in countries like Indonesia, Pakistan, India and other Asian countries. It was named “Green Revolution”. The novel technological development of the Green Revolution was the production of what some referred to as “miracle seeds.” Scientists created strains of maize, wheat, and rice that are generally referred to as HYVs or “high yielding varieties.” HYVs have an increased nitrogen-absorbing potential compared to other varieties.

The Cold War era after World War II was the political context for the Green Revolution. Introduction of HYV seeds promoted in the name of 'Green Revolution' was to confront 'Red Revolution' in Asia. All these were done in the name of increased food production for feeding increased population. To support such introduction of seeds, the fear of over-population was created. This also helped in convincing the bureaucrats and the ruling class. The claim was that “[t]he Wonder wheat and miracle rice developed in Mexico and the Philippines in the mid-sixties by the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations were hailed as the breakthrough that would save the World from starvation” (White, 1994). The International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) near Manila, Philippines was opened in 1962 “amid fear that because Asia’s population growth was outstripping its food production, there would be widespread famine. To avert such a calamity, IRRI did something of far reaching consequence. It transformed the rice plant. Height reduced from about five feet to three, so that when fertilizers makes for heavier panicles, or clusters of rice grain, the stalks won’t fall over. Growing period reduced from about 160 days to 110, so in warm climates, if irrigation is available to supplement seasonal rainfall, there can be two or three crops a year instead of one” (White 1994) . According to the Principal breeder Gurdev S. Khush, “in 25 years from 1967 to 1992 the world rice harvest doubled”. But what is left out of the discussion is how the increased yield of rice was achieved through a decrease in the production of other important food crops such as lentils, oil seeds were lost, and the overall loss of biodiversity.

However, in this process of solving the problem of hunger and starvation, the control over seeds by external agents, particularly by the Multinational Corporations is being established. The rice varieties that were available with the farmers and the communities in Asia are now found in the IRRI Gene bank. As Peter White puts it, “The building blocks for this science-directed evolution are the seeds in cold storage at IRRI’s Genetic Resource Centre – some 80,000 rice samples (White 1994). Similarly the huge collection of seeds is stored in U.S. Department of Agriculture National Seed Storage Laboratory at Fort Collins, Colorado, containing around 250,000 samples (Ausubel, 1994). The seeds are stored in freezing conditions, not being regenerated in the farmers’ field, therefore, have posed more threat of extinction than in the farmers’ field or in the wild. According to a plant physiologist at Fort Collins, “Within five or ten years, you may have lost half of the genetic materials you started with. Investigators in 1989 found that less than a third of its samples even germinated, making it not a seed bank but a “seed morgue”. Seventy-two percent had not been tested in five years (Ausubel, 1994).

The global centralized seed collection, however, does not ensure the wide range of diversity of crops. In fact it reduces diversity. So far, it is done mainly for cereal crops and some legumes (beans) and potatoes. Even among these crops, diversity is very small. For example, of the 1799 varieties of beans grown by the Seed Savers Exchange Network, only 147 were listed in the U.S. National Plant Germ Plasm system (Ausubel, 1994).

The Global Seed Vault: Privatization of Global Seed Collection

Although the earlier efforts of Global seed collection were initiated by government agencies such as Department of Agriculture in US, the initiatives in the present days have now shifted to private hands. Microsoft founder Bill Gates is finding more interest in seed banks. The first international effort to restore, organize and safeguard scattered seed banks holding some 165,000 varieties of the 21 crop plants is going to receive a $37.5 million infusion, a $30 million grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and $7.5 million from Norway (Acharya, 2008).

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault, or the Doomsday Vault as it is called by the media, is far from what a farmer in the developing country in Asia can imagine. According to the IPS report, it is built into the Arctic permafrost, with a natural temperature of minus 6 degrees centigrade, some 1,000 km away from the North Pole, has three cold rooms further cooled to minus 18 degrees C and is capable of storing 4.5million batches of seeds. Svalbard is a group of islands nearly a thousand kilometers north of mainland Norway. Remote by any standards, Svalbard’s airport is in fact the northernmost point in the world to be serviced by scheduled flights – usually one a day. For nearly four months a year the islands are enveloped in total darkness. It is here that the Norwegian government has built the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, to provide this ultimate safety net for the world’s seeds. The Global Crop Diversity Trust considers the vault an essential component of a rational and secure global system for conserving the diversity of all our crops (Acharya, 2008).

The view of Global Seed Vault from outside (top) and inside (below). The collection of seed from around the world was part and parcel to colonial adventure. In colonial missions it was manadatory to 'discover' biologcal world as well, like new lands, and collect and bring seed and genetic resources back to the colonial countries. This is 'biopiracy' that has hardly been covered in history books. Like 'botanical gardens' in the colonial countries, the idea of a seed vault is an old, pre-planned operation. It took nearly thirty years of planning. The facility is not only a storage space for seeds from all over the world, it’s a huge structure to boot, built in the permafrost of a mountain on Spitsbergen Island in the Arctic Island. Svalbard is a part of Norway. The Global Seed Vault has been designed to collect seed from around the globe and from nearly every variety of food crop on the planet, such as rice, wheat, or maize. Implicit in such idea, plan and its execution is the politics of fear, catasprophe and terror. The seeds and genetic resorces are not safe in the hands of the farmer communities who for millenium developed, conserved and regenerated them. Agrarian civilisation, knowledge of the farmer and their practices are being systematically destroyed and their biological resources are being pirated. It is not the industrial civilisation and the lifestyles of the so called 'modernity' is to be blamed – It now the nature and the human beings of the lowwer kins must be blamed for the imminent destruction of the world. So, in the arctice, the seed vault has been created. (Ed.)

The Barcelona-based advocacy group GRAIN says,' the GSV’s ex-situ storage system takes unique plant varieties away from farming communities that originally created, selected, protected and shared the seeds. Farmers, it holds, do not know how to access the scientific and institutional framework involved in setting up the system and are excluded'. (Acharya, 2008)

Genetically modified seeds

Green Revolution did not remain green. After having severe effects on soil, water, crop diversity, land ownership, loss of livelihood of farmers and yet no food self sufficiency, the initiators started talking about further improvements in seed technology. The Rockefeller Foundation that funded the research of HYV seeds and claimed that it will solve the problem of hubger never said sorry for the mistakes and blunders it has done to the agricultural systems in Asia, rather it is still trying to have corporate control over agriculture and food production by spent money in sponsoring research and development of GM crops to be deployed in world food production. During the period 1995 – 2005 Rockefeller spent over $100 million in GM crop research. They have specifically targeted key developing nations in their efforts. The Rockefeller Foundation is, in effect, the Trojan Horse of GM proliferation. According to Engdahl, “In June 2003, President George W. Bush made the issue of lifting an 8-year European Union ban on genetically modified (GM) plants a matter of US national strategic priority. This came only days after the US occupation of Baghdad. The timing was not accidental. Since that time, EU resistance to GM plants has crumbled, as has that of Brazil, and other key agriculture producing nations. One year before, the future of GM crops was in doubt.”( Engdahl , 2005)

Rockefeller Foundation’s interest in developing seeds with technology is not just out of its love for science. It is for national security of the United States. According to Engdahl, “In 1972 President Nixon named foundation board member, John D. Rockefeller III, to chair a Presidential Commission on "Population and the American Future." The same Rockefeller created the Population Council in 1952, and openly called for "zero population growth." Rockefeller's Commission on Population and the American Future laid the foundation for Henry Kissinger's National Security memorandum, NSSM 200, of April 1974, which cited population growth in strategic, raw materials rich developing countries as a US national security concern of the highest priority.” National security became tied to security of cheap imported oil, and food was a weapon in the US security arsenal from that time on. Kissinger's Cabinet colleague, Agriculture Secretary, Earl Butz, reflected the Kissinger policy when he stated, "Hungry men listen only to those who have a piece of bread. Food is a tool. It is a weapon in the US negotiating kit."

Bangladesh farmers protesting against GMOs. Such protests from the farming community also challenge the dominant idea that 'technology is politically, culturally and economically 'neutral'. The Global Seed Vault is a ginat and visisble structure that shows how seeds and genetic resurces are going to be owned and controlled by few countries and few multinational companies, similarly the proprietory genetically engineered seed is to destroy the farmer's seed system and carrying the danger to bilogically pollute Bangladesh irreversibly.

"NSSM 200 concluded that the United States was threatened by population growth in the former colonial sector. It paid special attention to 13 "key countries" in which the United States had a "special political and strategic interest": India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines, Turkey, Nigeria, Egypt, Ethiopia, Mexico, Brazil, and Colombia. It claimed that population growth in those states was especially worrisome, since it would quickly increase their relative political, economic, and military strength" (Brewda, 1995).

It is therefore not very surprising to learn that Rockefeller’s engagement in developing genetically modified seeds is also linked to US-led war in Iraq. According to Engdahl, “In June 2003, President George W. Bush made the issue of lifting an 8-year European Union ban on genetically modified (GM) plants a matter of US national strategic priority. This came only days after the US occupation of Baghdad. The timing was not accidental. Since that time, EU resistance to GM plants has crumbled, as has that of Brazil, and other key agriculture producing nations. One year before, the future of GM crops was in doubt”(Engdahl, 2005).

In post-invasion Iraq, U.S. diplomat L. Paul Bremer introduced to Iraq during his tenure as administrator of the Coalition Provisional Authority, the American body that ruled the “new Iraq” in its chaotic early days issued a series of directives known collectively as the “100 Orders”. Among them Order 81, officially titled Amendments to Patent, Industrial Design, Undisclosed Information, Integrated Circuits and Plant Variety Law was enacted by Bremer on April 26, 2004. What Order 81 did was to establish the strong intellectual property protections on seed and plant products that a company like the St. Louis-based Monsanto — purveyors of genetically modified (GM) seeds and other patented agricultural goods — requires before they’ll set up shop in a new market like the new Iraq. With these new protections, Iraq was open for business. It was no less than telling each and every Iraqi farmer — growers who had been tilling the soil of Mesopotamia for thousands of years — that from here on out they could not reuse seeds from their fields or trade seeds with their neighbors, but instead they would be required to purchase all of their seeds from the likes of U.S. agriculture conglomerates like Monsanto (Engdahl, 2005).

Control of seeds by MNCs

With more and more technological interventions in the seed the seed savers are replaced by multinational corporations. According to Godoy, ‘twenty-five years ago, there were at least 7,000 seed growers worldwide, and none of them controlled more than one percent of the global market. Today, after a takeover spree, 10 major biochemical multinationals, including Monsanto, DuPont-Pioneer, Syngenta, Bayer Cropscience, BASF, and Dow Agrosciences, control more than 50 percent of the seeds market’ (Godoy , 2008). The hundreds of thousands of seed savers, mainly comprising of women never claimed control over the seeds, rather tried to regenerate and exchange among the farmers, whereas when the corporations are controlling the seed market, it is patented without having any knowledge on the seed and only selling for profit.

The seed corporations only want control and dependency on them. Based on 2006 revenues, the top 10 seed corporations account for 55% of the commercial seed market worldwide. The market share of the top 10 seed companies is even greater when looking at the proprietary seed market (that is, the market for commercial, proprietary seed –subject to intellectual property). According to Context Network, the global proprietary seed market was worth $19,600 million in 2006.

- In 2006, the top 10 companies account for $12,559 million – or 64% of the total proprietary seed market.

- Monsanto – the world’s largest seed company – accounts for more than one fifth of the global proprietary seed market.

- The top 3 companies – Monsanto, Dupont and Syngenta – account for $8,552 million – or 44% of the total proprietary seed market.

- The top 4 companies account for $9,587 million – or almost half (49%) – of the total proprietary seed market. (ETC, 2007)

Once the biochemical industry giants are controlling the seeds, they are making them infertile. “You sow them this year, and that's it. For next year's crop, you need brand new seeds -- you would have to buy them, of course”. According to the report of IPS, quoting Benedict Haerling, researcher at the German non-governmental organisation Future of Agriculture "The goal of these companies is, of course, to make profits. In order to improve their profits, they all apply one strategy to increase their control of the market: they impose upon farmers worldwide the so-called vertical integration of inputs, from seeds to fertilizers to pesticides, all from one brand. Compulsory customer loyalty, you might call it” (Godoy, 2008).

One example of sterile seeds is Terminator (a.k.a. "genetic use restriction technology" - GURTs). These are plants which are genetically modified to produce sterile seeds at harvest developed by the multinational seed/agrochemical industry and the US government. Terminator seeds would prevent farmers from saving seeds from their harvest, forcing them to return to the commercial market every year and marking the end of locally-adapted agriculture through seed selection. Debra Harry of the Indigenous Peoples Council on Biocolonialism, and member of the expert group that examined the potential impacts of GURTs (Terminator) on indigenous peoples, smallholder farmers and Farmers' Rights said, "Terminator technology is an assault on the traditional knowledge, innovation and practices of indigenous and local communities. Field testing or commercial use of sterile seed technology is a fundamental violation of the human rights of Indigenous peoples, a breach of the right of self-determination."(ETC, 2006)

From the seeds, the entire food supply is becoming concentrated in the hands of few multinational companies. According to Richard Freeman of Executive Intelligence Review, only ten to twelve pivotal companies, assisted by others, run the world's food supply. They control the world’s cereals and grains supplies, from wheat to corn and oats, from barley to sorghum and rye as well as meat, dairy, edible oils and fats, fruits and vegetables, sugar, and all forms of spices. They are the key components of the Anglo-Dutch-Swiss food cartel, which is grouped around Britain's House of Windsor. Led by the six leading grain companies—Cargill, Continental, Louis Dreyfus, Bunge and Born, André, and Archer Daniels Midland/Töpfer—the Windsor-led food and raw materials cartel has complete domination over world food supply.

Each year tens of millions die from the most elementary lack of their daily bread. This is the result of the work of the Windsor-led cartel. And, as the ongoing financial collapse wipes out bloated speculative financial paper, the oligarchy has moved into hoarding, increasing its food and raw materials holdings. It is prepared to apply a tourniquet to food production and export supplies, not only to poor nations, but to advanced sector nations as well (Freeman , 1995).

Food sovereignty

At the backdrop of the control of seeds and thereby the food system in the hands of the multinational corporations, farmers around the world started fighting back. While they started to look at the possibilities of having their own control over seeds, and farming practices, they also started fighting against biopiracy, patenting of seeds, and against the notion of market solutions for solving hunger. In this process, the global movement of farmers showed interest in launching the term food sovereignty. The concept of Food Sovereignty was launched challenging the concept of food security by Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) at the 1996 World Food Summit held in Rome, Italy. The mainstream definition of food security is deceptive and talks about everybody having enough good food to eat each day. It talks about availability and accessibility but not about where the food comes from, who produces it, how under which conditions it has been grown. In other words they help the food exporters, in North and South, to argue that the best way for poor countries to achieve food security is to import cheap food from them, rather than trying to produce it themselves. Food security definition therefore is against the farmers and in favor of the traders.

The South Asia Network on Food Ecology and Culture (SANFEC) since its inception in 1996 critically looked at the notion of food security and promoted the notion of food sovereignty. In its Statement of Concern published in 1996, SANFEC said, 'We believe that food security has different meaning in the North and the South. In the South, it essentially means availability of food under adverse conditions, and physical access to alternative "natural" sources of food. These naturally available food can be `harvested' as common property resources and often remain available to the community as last crops under stress conditions (SANFEC, 2001).

According to SANFEC, in the North, the question of "food security" is essentially tied up with the concept of exercising command and control over other nations and communities. Therefore, it is linked to the domination of the world production of food, through global food market. Food was always used as a political weapon to assert domination since colonial era. In the post-colonial period, the use of food as weapon continued to ensure the "security" of the dominating countries. The food aids through PL480 and Common Agricultural Policy as well the nature of the Uruguay Round negotiations on agriculture are clear examples what northern states mean by "food security". It is time that on behalf of South Asian communities we squarely challenge the politics of food security and turns it to express what it should indeed mean now. That is, freedom of communities from the global domination of food production and food marketing by few nations through a handful of transnational agro-business companies. Food security of the world population can only be ensured by secured food producing communities who exchange their articles of need and surpluses for mutual convenience and gains (SANFEC 2001).

Via Campesina, the international farmer's and peasants' movement launched the concept at the 1996 World Food Summit in Rome. In 2001, the 'World Forum on Food Sovereignty ' was held in Cuba and a year later, at the NGO/CSO Forum on Food Sovereignty held alongside the second World Food Summit in Rome, the concept was further discussed and elaborated. Unlike food security, which suggests only that people have enough to eat but fails to address who produces it or how, food sovereignty emphasizes the right of each nation to protect and regulate domestic agricultural production and trade to achieve sustainability, guarantee livelihood for farmers, and assure that its citizens are fed. As such, farmer and peasant groups like those who form part of the Via Campesina, consider food sovereignty to be a matter of national security (Rossett, 2003).

Nayakrishi Andolon: Popular Resistance Movement of Farming Communities

Nayakrishi Andolon literally means New Agricultural Movement of farming communities. Farmers are practicing 10 simple rules[2] of biodiversity-based ecological agriculture to achieve joyful, prosperous, and secured life. The sovereignty over food production and seed systems is the strategic area of work to achieve the goal. Nayakrishi insists on dissolving the divide between ‘formal and ‘informal’ knowledge practices to shift the paradigm of food production. As a general practice farmers of Bangladesh keep seeds in their household for the next season. Nayakrishi strongly encourages this tradition of the farmers. Control over seed is the lifeline of the farming community and ensures the command of the farmers over the agrarian production cycle. It is recognized within the Nayakrishi Andolon that break in the cycle within the circuit of circulation of seeds among farmers can be highly detrimental to the overall agro-biodiversity of the production systems. In the light of the increasing commercialization of seed sector the danger has aggravated in the recent years (Mazhar, 2008).

Community Seed Wealth (CSW) is the institutional set up in the village that articulates the relation between village and the National Gene bank. The CSW also maintains a well-developed nursery. The CSW can easily finance its maintenance from the income of the nursery as well as from seed sale. The construction of CSWs is based on two principles: (a) they must be built from locally available construction materials and (b) the maintenance should mirror the household seed conservation practices. Any difficulty encountered in the CSW reflects the problem farmers are facing in their household conservation (Mazhar, 2008).

The simple technique of seed keeping based on thousands of years of experiences is a real challenge against the global seed vaults. Farmers, particularly women, are the real custodians of the seed in the farming communities. As Grain puts it, after their visit to one of the seed wealth centers of Nayakrishi Andolon, “Hundreds of communities in many different parts of the country use the seeds every season, keep them safe in their homesteads, and a sophisticated exchange and monitoring network of the villagers ensures that at any point in time thousands of different seed varieties are being grown and kept alive, somewhere. At some point in the discussions, someone asked the question what they understand by food sovereignty. One of the women pointed to the seed centre behind her, smiled, and simply said: 'this' (Grain, n.d.)

Conclusion: How threat to seeds poses threat to national security and Peoples’ Sovereignty

What is clear from above is that threat to life and life support systems is directly linked with seed and genetic resources. When farmers' movements such as Nayakrishi Andolon raise the question of 'sovereignty' they particularly highlight the need to defend life in general and the need to defend radical cultural practices that are consistent with life affirming activities that critique neocolonial globalism. This is the key element in understanding the new discourse of sovereignty that cannot be grasped simply by the paradigm of political science. This 'sovereignty' cannot be defended by the conventional nation-states, but through networks of peoples’ movements challenging the role of States in promoting the interest of corporations, industrialization and consumerism.

Food has always been used as a political weapon. Challenging the monopoly control of corporations is important in this struggle but not sufficient unless we strategically organize our movements around seed, genetic resources and life affirming knowledge practices. We also need to make clear distinction between seed which is alive and symbolizes the potential life process on its own against the so called “seeds” produced by multinational corporations like Monsanto, Syngenta, Bayer, and DuPont which are 'inputs' without any capacity to reproduce. Therefore, calling them “seed” simply confuses the issue.

We could also see that concentration of genetic resources in one centre is a major threat because the farmers will have absolutely no control over the collection. The question of 'sovereignty' takes a new global significance in contrast to such seed vaults. Sovereignty in this sense is not local, but rather based on the preservation of life and life affirming activities against the forces of rampant destruction across nation-states.

Farida Akhter is the Executive Director of UBINIG (Policy Research for Development Alternative and the one of the leading figures of women's movement in Bangladesh.

References:

|

CCIC 1975 |

Canadian Council of International Cooperation, “Canada and the Food Issue” (Toronto, Canada: Gatt-fly and the United Nations Association of Canada, 1975) in Population Target: The Political Economy of Population Control in Latin America, by Bonnie Mass, LAWG, Canada, 1976

|

|

White 1994 |

Rice the Essential Harvest, by Peter T. White, National Geographic, May 1994 |

|

Ausubel, 1994 |

Seeds of Change: The Living Treasure; The passionate Story of the Growing Movement to Restore Biodiversity and Revolutionize the Way we think about by Kenny Ausubel, HarperSanFrancisco, 1994 |

|

Acharya, 2008 |

NGOs Wary of Doomsday Seed Vault, by Keya Acharya, IPS, March 4, 2008 |

|

Engdahl, 2005 |

Seeds of Destruction: The Geopolitics of GM Food by WILLIAM ENGDAHL / Current Concerns (Zurich) n.5, 6mar2005 |

|

Brewda, 1995 |

Kissinger's 1974 Plan for Food Control Genocide by Joseph Brewda, http://www.larouchepub.com/other/1995/2249_kissinger_food.html

|

|

Godoy, 2008 |

Privatisation Making Seeds Themselves Infertile, Julio Godoy May 22, 2008, Inter Press Service) |

|

ETC, 2007 |

ETC group, April 30, 2007 |

|

ETC, 2006 |

Terminator Threat Looms: Intergovernmental meeting to tackle suicide seeds issue Intergovernmental meeting to tackle suicide seeds issue CBD's Working Group on 8(j) Meets in Granada, Spain 23-27 January, 2006 ETC Group, News Release 20 January 2006. |

|

Freeman, 1995 |

Windsor’s Global Food Cartel: Instrument for Starvation by Richard Freeman, Executive Intelligence Review, December 8, 1995 |

|

Rosett, 2003 |

Food Sovereignty: Global Rallying Cry of Farmer Movements by Peter Rosset, Fall 2003 http://www.foodfirst.org/pubs/backgrdrs/2003/f03v9n4.html) |

|

Grain, n.d. |

http://www.grain.org/seedling/?id=329 Food Sovereignty: turning the global food system upside down by GRAIN |

|

SANFEC, 2001 |

South Asian Statement of Concern on Food, Ecology and Culture and other documents of SANFEC Published by: Narigrantha Prabartana, Bangladesh 2001 |

|

Mazhar, 2008 |

Nayakrishi Experience: Addressing Food Crisis through Biodiversity-based Ecological Production Systems by Farhad Mazhar, UBINIG Presented at One Just World Forum Series: Will the world be able to feed itself in 2050? Food security and the developing world. Wednesday 10 September 2008. Adelaide Town Hall, Presented by World Vision Australia, International Women’s Development Agency and AusAID, and supported by The Bob Hawke Prime Ministerial Centre, UniSA. |

[1] Prepared for 7th Asia-Europe People’s Forum, Beijing, China during 12 – 15th October, 2008 organised by One World Action

[2] Ten Rules are: (1) absolutely no use of pesticide (2) in situ and ex situ conservation of seed and genetic resources, (3) production of healthy soil without external inputs, particularly chemical fertilizer, (4) Mixed cropping (5) production and management of both cultivated and uncultivated spaces (6) no extraction of ground water and conservation of water and efficient surface water use and management (7) learning to calculate the output both in terms of single species and varieties as well as system yield (8) Integrating livestock in the household to produce more complex household ecology to maximize benefits and well being of both humans and life forms (9) Integrating water and aquatic diversity to generate more ecological products and (10) integrating non-agricultural rural activities to ensure prosperity of the local communities as a whole.